Who hasn’t wondered how a board game is created and graphically realized? Benjamin Schwer takes us on his very personal journey with Djinn.

“The basic idea of Djinn goes back to a game of Trajan (by Stefan Feld) in late fall 2017. After the game, I thought about how successful it was to incorporate an interesting core mechanism into a game without this mechanism being directly related to the theme and the actions that the players perform. This consideration finally led me to an idea for a game based on three central ideas. But first to the question of the topic:

Topic

As titles and themes are often decided by the publisher, in this case I was first concerned with setting up the game system. I deliberately chose a generic theme for the development and test phase because, in my experience, a game with a familiar theme can be accessed more quickly. So I chose historical Rome and simply called the game Rome.

1. The core mechanism

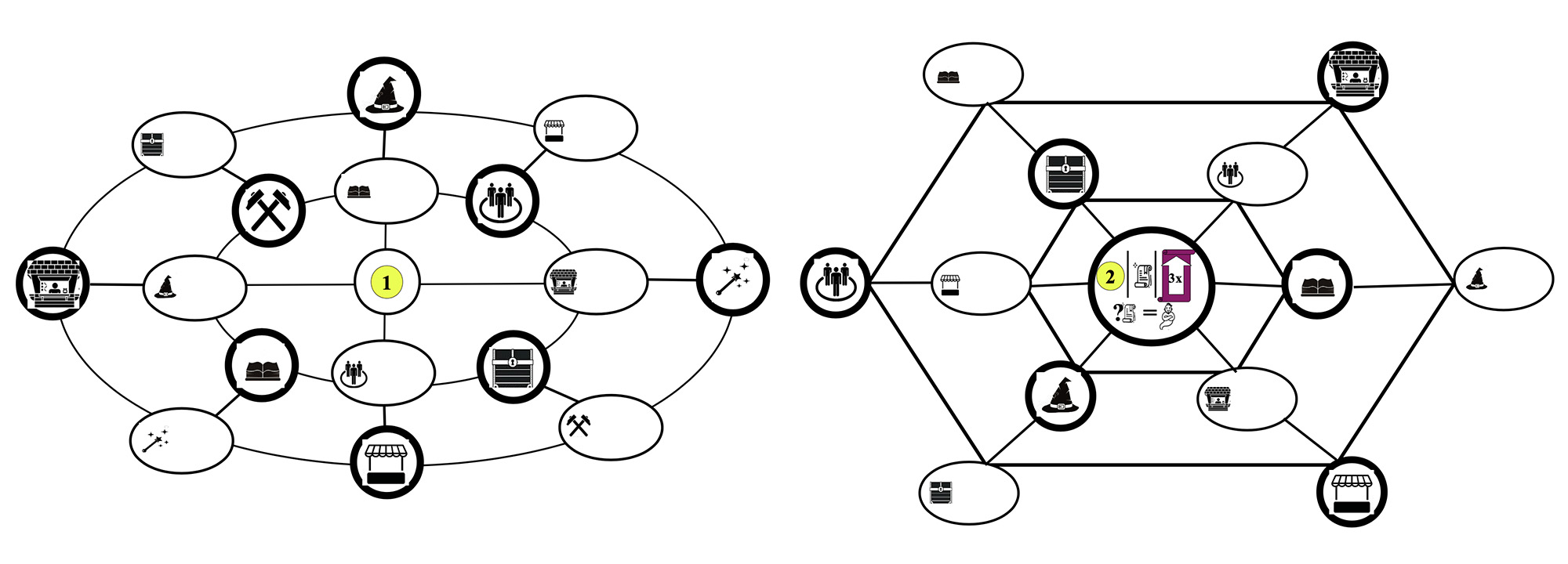

I first thought about which fundamentally abstract mechanism I would personally like to see in a modern board game and which, if possible, has not yet been used in this way. So I came up with the idea of moving a knight from chess to a 4×4 board. I had never seen this way of reaching the squares in a modern board game before. I particularly liked the fact that it offered control and predictability. (Note: There is a similar mechanism in the game Robin von Locksley by Uwe Rosenberg from 2019. I wasn’t aware of the game at the time).

I then assigned actions to the fields. I realized that 16 different actions would be too many, so I decided on eight different actions, each of which would be available in a strong and a weak version. The alternating strong/weak arrangement resulted in the interesting effect that a weak action was always followed by a strong action. With little effort, this resulted in a lot of game depth all by itself.

In this first version, all players had their own, individually arranged game plan. The same actions were basically available on all plans, but not in the same order. I also added the option of improving your own tableau during the course of the game, i.e. adding a marker with another small action at locations with small actions. The next time the knight came to such a modified square, both small actions were usable.

2. Few victory points

Another central idea was that there should only be a few ways to score victory points and that every victory point should feel important. In Rome, the initial theme was to obtain the most “golden seals” as a sign of recognition for services rendered to the Roman Empire.

These golden seals could be achieved directly by completing certain tasks, such as successfully exploring land or shipping goods. However, gray seals were much more common than golden seals and were therefore much easier to achieve. In the course of the game, these could be converted into golden seals according to an exchange rate to be earned. The game was designed in such a way that only a small number of golden seals could be collected by the end of the game.

3. Influence on the end of the game

On the original eight individual action boards, which were placed on the table in addition to the players’ game boards, goods could be produced and shipped, the military reinforced and deployed for exploration, taxes collected, nobles recruited, the position in the senate improved and buildings and statues constructed.

Special actions were the buildings and the senate: Constructing buildings did not yield as much in the game as other actions, but you could only take part in the final scoring if you had constructed at least five buildings. Thematically, this was intended to symbolize that the players also had to take care of the further development of Rome and not just pursue their own plans.

The Senate had two relevant functions: On the one hand, players could improve the exchange rate for their gray seals there. On the other hand, this offered the opportunity to trigger the end of the game prematurely if you progressed quickly – an important aspect for long-term strategies.

Part 2 – Revision with Ralph Bruhn

I introduced the game to Ralph Bruhn in early 2019, who owns his own publishing house, Hall Games, and also works a lot with Pegasus Spiele as a freelance editor. I had previously worked with him on the Yeti and Crown of Emara games, both published by Pegasus Spiele, and was very happy with them. I found the constructive cooperation with Ralph particularly pleasant.

At the time, neither Ralph nor I could have foreseen how intensive and lengthy the reworking of the game would be. The fact that Rome didn’t appear as Djinn until four years later was mainly due to the fact that the coronavirus pandemic slowed us down considerably during development. There was a lack of feedback from test rounds to identify and eliminate the weaknesses of the design.

For a long time, we had to limit ourselves to just a few digital test rounds on Tabletopia. But testing is not just about seeing whether the mechanisms work, but also about assessing whether the players have fun playing. And I have to admit that I found this difficult, as the playing time in the digital rounds was significantly longer than at the gaming table, which had a negative impact on the gaming experience.

When we finally had “real” testing opportunities again, the feedback gave us some good ideas for getting even more out of the game. Incorporating the changes ultimately took another year.

To give a complete overview of everything we have changed, rethought, rearranged, tried out, discarded, discussed and implemented in the various phases of the revision would go beyond the scope of this article. Therefore, in the next part, I will focus on what has become of the three central ideas and the topic mentioned above.

But I can already say this much: we have removed the punishing elements and some of the luck elements that were initially present. For example, you had to have built at least five buildings by the end of the game to even make it into the final ranking. These changes came as no surprise to me, as I already knew from working with Ralph in the past that he attaches great importance to conveying a positive basic feeling in games.

Part 3 – What became of the topic and the three basic ideas from the beginning

On the topic

Ralph changed the theme after just a few months and chose a magical setting. The working title at the time was ” genies in a bottle” for a very long time. The title was also a wonderful indication of what the players’ specific task should be: Now it was about capturing ghosts.

The golden seals became ghosts that were worth nothing if you couldn’t catch them in bottles. The eight individual actions were thematically adapted and gradually developed further and finally reduced and optimized to six actions.

Re 1. the core mechanism

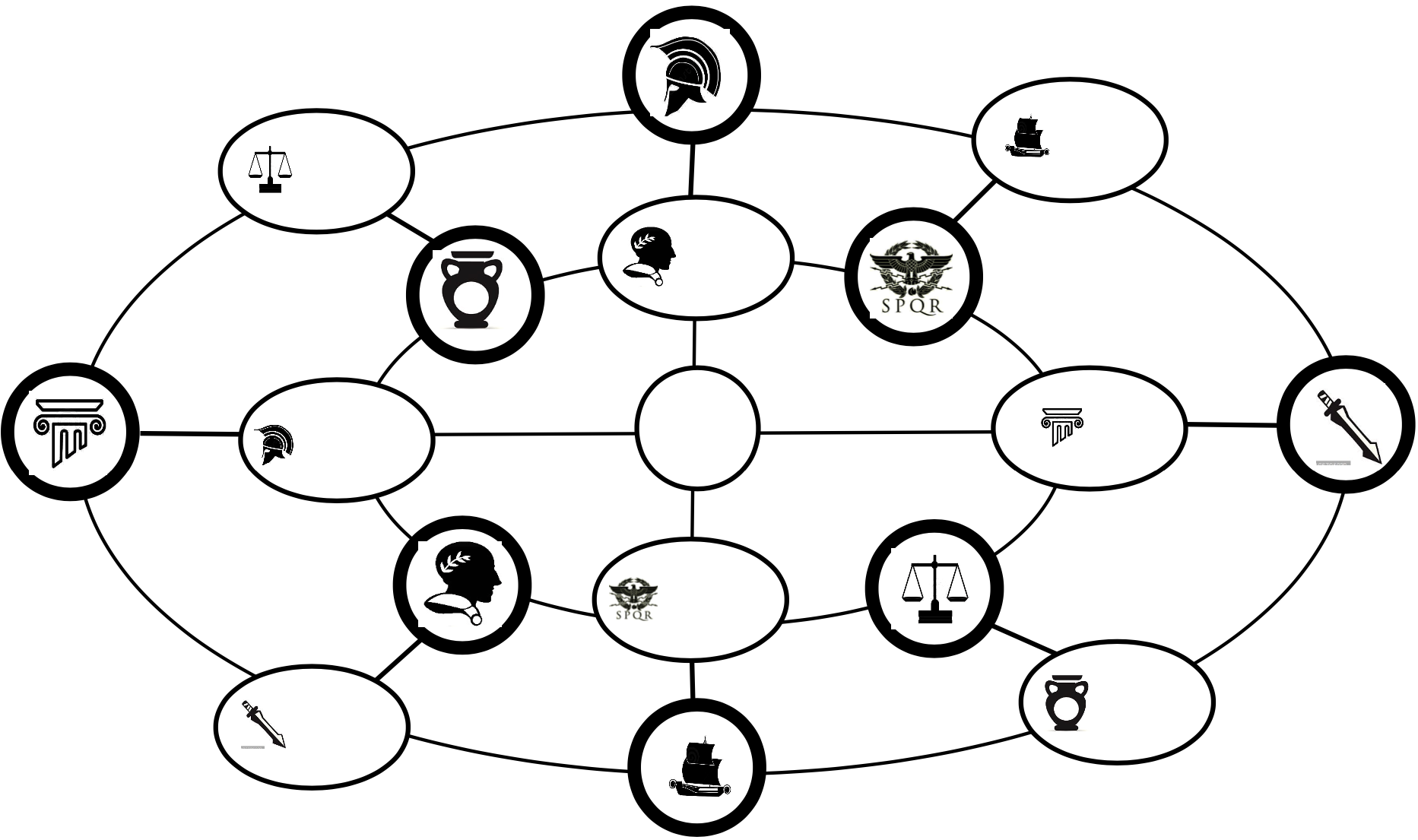

Mechanisms that are special and unusual sometimes have the disadvantage of being difficult to play for some people. The original 4×4 grid was ultimately too confusing for many players to be able to plan the paths of a knight in advance and thus put the actions in a sensible order.

Ralph had a good idea how to arrange the basic idea topologically equivalent (i.e. change from strong to weak with 2-3 options for the next move), but much clearer:

This arrangement had several advantages: the previously disadvantaged corner squares were now equal in terms of the number of connections; we were able to integrate an additional square in the middle; we were now able to solve the problem of jumping back and forth between two squares; we were later able to reduce the system from 16 to 12 squares. That’s why we replaced the knight move early on with a piece that was never allowed to move backwards.

We also considered the idea of a joint game plan instead of individual plans for the players, but initially rejected it. It seemed too confusing and too big. There also had to be room for the individual upgrade markers and the Djinns.

But then came the post-corona feedback with some wishes and suggestions: the paths should be shortened, the actions should feel more varied and the game should be a little less solitary and therefore less predictable. So we completely restructured the activities and reduced them from eight to six, which allowed us to switch to a joint game plan after all. This has enabled us to both increase interaction and improve clarity. Even the Djinns, which were previously on the action plans, still had space next to the round squares on the game board.

We have also further upgraded the originally uninteresting starting field in the middle and modified it into a special action field of equal value:

Re 2. few victory points

The aim of the Djinn game was therefore clear and simple: who could catch and cork the most Djinns in bottles? For a long time, this was the only score that could be quickly determined at the end; corks and empty bottles were only tiebreakers.

Since you could catch about ten Djinns per game, catching every single Djinn felt good and rewarding. On the other hand, however, this also meant that the tiebreakers had to be used relatively often in the scoring, which could sometimes give the impression of arbitrariness. Therefore, we now convert the three elements Djinns/bottles/corks into points at the end of the game, although in most cases the greater number of Djinns caught leads to a win. On the one hand, this had the advantage that the impression of arbitrariness no longer occurred, and on the other hand, we were able to integrate the scoring cards as an additional element.

3. influence on the end of the game

In the first versions of the game Djinn, there were several ways to actively initiate the end of the game. This could lead to frustrating moments as the game ended unexpectedly for some.

We were able to solve this problem by linking the end of the game solely to when the six Meisterdjinns are removed from the village. On the one hand, this is entirely in the hands of the players, which was my aim from the outset. Secondly, it is very clear because everyone can see at any time how many Meisterdjinns are still in the village and who has the opportunity to reach them.

In addition, the game does not end immediately after the end-of-game condition is triggered, but everyone still has 1-2 more actions in which one or the other plan can be completed or resources can be converted into points.

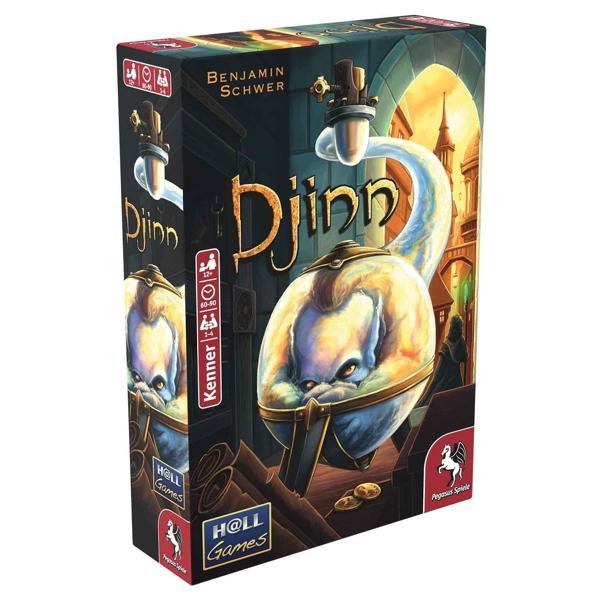

Part 4 – The illustration

I was delighted that Dennis Lohausen had agreed to illustrate the game. He did a really wonderful job on the graphics for Yeti and Crown of Emara and I was very curious to see what kind of visually appealing work of art he would create this time.

Even the first cover designs showed an exciting direction and with each new illustration the magical world of the game became more tangible.

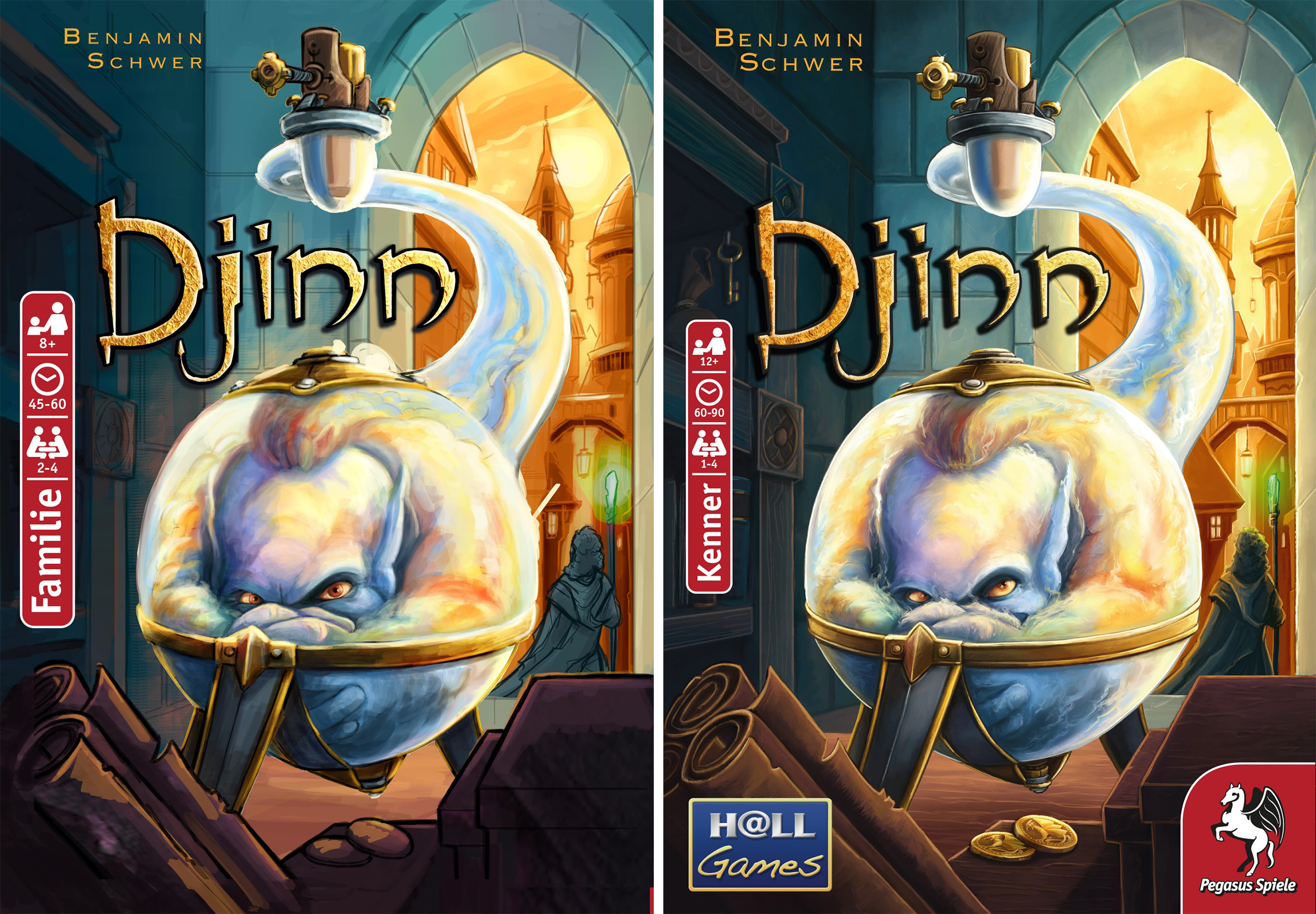

To give you an insight into the illustration process, here’s an example of the Djinn’s design: the Djinn shouldn’t look so nice that you feel sorry for him, after all, we’re supposed to capture him. But it shouldn’t look so evil that you feel put off by the cover.

Dennis has created several versions with facial expressions, including one where the Djinn in the bottle is staring directly at us. On the one hand, I thought that was great, but on the other hand, there was also something hostile about the Djinn’s look, which put some people off. The decision was therefore ultimately made in favor of the right-hand design:

Dennis has also done a great job with the game materials: the design allows us to immerse ourselves in the story of the game and at the same time the clarity has been optimized once again.

What was still a central game board with six action boards around it in the prototype has been combined into a large overview board, but the strict rectangle of a game board has been loosened up by recesses into which cards and tiles can be docked.

In conclusion, I can say that the development of Djinn has been a long and labor-intensive, but above all a very interesting, varied and exciting journey.

I would like to thank everyone involved who contributed to and enriched this game in so many different ways.

I hope that all readers have enjoyed this brief insight into the development history of Djinn and wish all future players lots of fun with the game.”

Djinn

-

- Number of people:for 1 to 4 players

- Age: from 12 years

- Playing time:70 to 90 minutes

Author: Benjamin Schwer – Source: Pegasus Blog

Find out exciting news and more about our products every week at varia.org/blog !